Tarpon U.S. Equities – 2020 Annual Letter

Guilherme Partel, Tarpon U.S. Equities team

Our first year in business was quite eventful to say the least, but I will spare you another text on how Covid-19 has shaken up the world, impacted businesses differently, accelerated everything, created political turmoil, and led to the K-shaped economic recovery. I will instead use the precious time you are dedicating to read this letter for matters more specific to our portfolio and long-term roadmap.

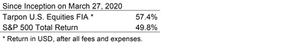

In the middle of the hurricane, on March 27, we launched our first fund, Tarpon U.S. Equities FIA, in Brazil, but whose assets are totally invested abroad according to our reason-of-being. Our offshore fund came a bit later, in August, but our seed-money investors, Tarpon’s partners, already had sizable sums in our portfolio in another offshore structure by that time (this investment was transferred to our new fund at launch). Both of our funds have identical portfolios and fees; hence we are reporting here the results for the oldest one, whose inception was close to the moment our total AUM really gained some scale, our portfolio took shape, and Zeca began to dedicate a lot of time to help me on each individual decision. (For clients of either fund interested in further details about your specific results, please contact us.)

About the results, it is so short a period that I cannot make any comments other than remember those who have been reading our articles on technology and digital businesses, that we own some companies whose operations and share prices have been, and remain, negatively affected by the pandemic, such as Capital One (a credit-card/online deposits bank) and 4Imprint (an online distributor of promotional products, which are often used in conventions and other in-person interactions). We also have about a quarter of the fund in residential broadband companies, which have very resilient free cash flows, as their cable wires are the backbone for our digital lives; but they are not the sort of business that exploded upwards during the pandemic. Moreover, some of our software companies, such as Intuit and Autodesk, despite having resilient businesses, could not escape the damage this crisis has brought to their clients, all sorts of small businesses and the construction industry, respectively.

We will have down years. We will occasionally trail the S&P. We will not try to optimize for short term results – we do not even know how to do that.

Our main investments:

With the caveat that fourth quarter results are still not out, we bring bellow some comments about the year for our main holdings, especially those to which we introduced you in our initial letter last year (https://www.tarponusequities.com/post/first-annual-letter):

Charter (through the holding company, Liberty Broadband): I am a shareholder at Charter since 2014. Back then I saw a huge runway for broadband penetration with it becoming essential to most households, as well as continued market share gains from competitors with weaker technologies. I, and almost everyone else in the market, have always assumed growth would gradually decelerate as the business matured, but we are still waiting for that. Due to work, play and everything from home, 2020 has been the best year for this company since I have been following it for almost a decade. As of Q3 broadband customer growth was up 9% from a year earlier, and operating earnings have likely increased at least 10% for the year. This is relevant growth for a company whose free cash flows enable it to retire almost 10% of its shares annually, at current prices.

WIX: Over 2018 and 2019, WIX was busy evolving its business model, trying to attract more valuable clients, as well as more high-end professional website designers. The company was focused on technology improvements and launching new features, such as payment capabilities and tools for SMBs to interact with customers online (video, events, scheduling, marketing, etc.). With this and a huge brand that dominates the online environment (Google, blogs, communities) about website design, WIX was greatly positioned for all that happened in 2020. Net new subscriber growth has roughly doubled from 2019, and prospects remain interesting with more than five million SMBs (and growing) having a core part of their operations on WIX.

GoDaddy: Despite surfing some of the same tailwinds as WIX, GoDaddy has more product lines and had to cut some high-touch services during the year, bringing some noise to revenue growth and investors’ perception; but the core, high-margin businesses are growing better than expected, margins are improving and the company continues to not only deliver big free cash flows, but also use them intelligently, doing some well-timed buybacks, for example.

Capital One: With a large credit-card portfolio, Capital One took a big hit over the first half of the year as it built loss allowance reserves. This had the effect of roughly erasing profits for the whole year. Nevertheless, the bank is very solid in capital terms, actual charge-offs have yet to materialize, and management’s long-term plans (to which we subscribed) of fostering digital relationships with consumers and moving the company to the cloud not only is intact but should bear good results sooner or later – the bank was running well, growing and with ROE approaching 15% pre-Covid.

Amazon and PayPal: With no introductions needed, these companies are newer investments to me, though I have been studying them for years and, thus, was ready to pull the trigger when, early in the pandemic, our partner Pedro Faria, told us sales were hugely accelerating at Petlove (Tarpon’s private equity online pet e-commerce investment). At that moment, shares of both Amazon and PayPal were being hit along with the market, and we saw the open door to finally realize a long-held desire to own them. We are in for the long-term – we would not have invested otherwise – and were pleased to see not only the strong growth throughout the year, but also the advance of strategic developments, such as PayPal’s digital wallet Venmo gaining additional functionalities, or Amazon’s AWS succeeding with its own chips that already bit Intel’s for some functions in cloud computing.

4Imprint: As hinted above, this company was hugely impacted by the crisis, with revenue likely falling between 30 and 40% for the year. Management has done a great job maintaining investments in the brand, avoiding layoffs, and holding operating results close to breakeven. Sooner or later the promotional products market will rebound, to which extent is still unclear to us, but with less than 5% market share in a sector still mostly offline, great cost advantages, and a well-oiled machine, 4Imprint should do well over the long run.

Before moving on to some more abstract paragraphs, I would like to introduce our advisory board, which meets monthly to review investment ideas, as well as our portfolio, provide feedback, make challenging questions, and help us in varied ways, such as connections: Zeca Magalhães, Pedro Faria, Eduardo Mufarej, Marcelo Lima, Vasco Oliveira, Rafael Maiosonnave, Caio Lewkowicz, and Chas Cocke.

************

I want to take the rest of the letter to cover a theme Zeca, I, and our partners have been discussing over the last many months and will be a big part of our future.

Convexity

Not even the most imaginative Amazon investor in 2010 could have foreseen what the company is now. And we are not here to make dreaming of our jobs. But a rational investor could have identified elements in that 2010-Amazon that pointed to a good likelihood of positive, out-of-the-blue outcomes. Amazon was led by a visionary founder (who had already set himself apart from the bad class of “visionaries”, such as Elizabeth Holmes, from Theranos), had proved it had a strong, customer centric and innovative culture, had already done audacious things challenging larger businesses, had great customer relationships, had opportunities to expand horizontally and vertically in big markets, and was, undoubtedly, at the technological forefront. Certainly, there were companies with similar characteristics in 2010 that ended up not delivering nearly as much, or even going nowhere. But even if an investor took five or ten similar sized shots to hit Amazon once, his results would be great, had he had the discipline not to sell along the way (which could be a topic for a whole other letter).

Amazon was, perhaps, the most convex big-business outcome of the last two decades; and it is too much to hope we can pinpoint anything similar. But we can have a rational, fact-based approach to investing that is more likely than not to land us convex outcomes, rather than concave ones.

Another, closer to home example for most of our readers is Stone, the Brazilian acquiring firm. When Berkshire Hathaway invested in Stone’s IPO in 2018, many local investors could not understand it, worried that merchant acquiring was quickly becoming a low margin business from looking at day-to-day news of price wars as incumbents responded to entrants’ aggressive growth. Berkshire (I guess), however, took a step back, looked at the forest rather than the trees, eyed the long-term and saw a great team and culture who had already proved their execution capabilities, as well as a huge, profitable, and slow-moving market to disrupt in banking services to SMBs, not to mention the potential of cross selling software, all of which are already materializing. But let me close this paragraph with the caveat that the jury is still out on Stone.

If all you do as an investor is look for a simple 8-10x earnings company, usually already using some financial leverage, and preferably in a slow-moving industry, odds are high you will end up making 12% a year at most over a reasonably long period of time. And that is just until disruption or some major societal forces come, unraveling that tranquility you bought in. Think about what Netflix has done to media companies like Viacom, or what growing environmental consciousness has brought to the coal and oil industries.

On the other side, if you are willing to study deeply, focus on the more complex qualitative topics first, and really sift-through hundreds of promising companies to select a handful of ones for which you can pay up confidently that they have high chances of delivering a lot over the next ten years (so that you can have a conservative expectation of making 8-9% returns), then you have exposed yourself to the possibility of convex outcomes, as these are the kind of companies that will often have the characteristics mentioned above about Amazon in 2010 – and especially so if you actively look for these features.

The process above described must be broken up further: what we are doing here when looking for new investments is somehow opposed to what the human mind would naturally do, prone to overconfidence and weak with statistics as we all are. Rather than trusting we “know” the future and simply buying into the “obvious and certain” 12% return on investments like the first example, while ignoring the (normally correct) wisdom of the crowds that this 12% return just exists because a good chunk of these companies is, sooner or later, going downhill, we are humbly trying to position ourselves to benefit from some uncertain convex outcomes, while trying to minimize risks.

The market also knows that those 8-9% returns underestimate the total return that group of firms will deliver in the long run, exactly because a few of them will be big outliers, an outcome no financial model can capture today, and more than offset losses from those that fail to live up to expectations. Some investors are great at beating the market by selecting the 12% returns that will not derail, or at least by selling out before they do. Our strength is at selecting a few “going somewhere” companies to own for the long run (as defined in our guiding principles that can be found here: https://www.tarponusequities.com/post/first-annual-letter), not trying to time the market, and increasingly at positioning ourselves for convex outcomes; in other words, to sift-trough the 8-9% universe and select a few cases we see not only as more reliable, but also better positioned for the future.

Coming back to risk minimization, which is paramount: we are not simply investing in any company or going along with any dreamer CEO that brags about unlimited potential. To the opposite, we begin with the basics: why can this business grow and deliver large returns with so much capital out there to fund entrants? What protects it? Can we really have enough confidence in a reasonable range of conservatively estimated scenarios that would give us downside protection? For each kind of business these answers can be found (or not) in different sorts of competitive advantages; good examples are in our June 2020 piece about software firms, some of which we own. It can be found here: https://www.tarponusequities.com/post/software-june-12-2020.

Risk minimization is also an exercise of discipline. Patience to just pull the trigger when the analysis is done, avoidance of high-profile companies without substance, such as WeWork, and an ability to simply say NO to most ideas that cross our minds are all necessary.

Another interesting aspect around this topic is the capital structure. We often come across companies that pass our barriers for quality, durability, and predictability in subscription/recurring business models, which are exactly the ones that could use some leverage to amplify equity returns. But leverage is concave. Cash is convex. Highly leveraged firms often find themselves in a tough spot, unable to invest during a downturn, for example. Cash rich companies, on the other hand, under-optimize results during periods of calm waters, and more than offset that when the storm, or a great opportunity, arrives.

Leverage is also a topic for a whole other article – we own a few companies that use leverage appropriately in our opinion, as they have growing, resilient and recurring revenues, as wells as high operating margins; on the other hand, we do not see high odds of convex outcomes from them. Nevertheless, we wanted to bring these few lines on capital structure, as it provides a nice example of the advantages of positioning oneself for convexity, which can just be done by those who are really willing to think long term, forgoing the instantaneous boost leverage can bring, or the great “sugar-high” feeling that buying into that “sure 12% return” gives.

Bringing all of this to an end, at concave companies, executives are worried with debt covenants and cost cuts, rather than thinking about new products, investments, and growth, such as their peers are doing at convex businesses. Software engineers are fixing legacy systems and bugs, rather than writing fresh code and designing great user experiences. Customers are complaining instead of looking at the brand as an aspirational one. Reported earnings are adjusted for items like restructuring expenses, idle plants, and layoff costs, rather than stock-based compensation, which is in good part an investment to attract top notch talent – a real and costly, but often rewarding form of capital allocation. Investors are asking about profits, leverage, and buybacks, rather than new projects and growth avenues, eventually creating a positive feedback loop that enables convex firms to invest more, fire more bullets, err more, and, maybe, hit it big.

I would like to close recognizing how much Zeca has contributed to the clarity of thought regarding all I just wrote, and with a special thank you to my long-time friend Claudio Skilnik who called my attention to the term convexity during a lunch in 2019, leading me later to clarify disorganized thoughts I had.

We appreciate your attention and partnership,

Guilherme Partel

Tarpon U.S. Equities

January 2021

- Who?

- Most read

-

-

Howard Marks e nossas reflexões sobre mercados de Nicho

1234 days ago -

Saúde Mental. Invista na sua

1261 days ago -

Tarpon U.S. Equities – 2020 Annual Letter

1292 days ago -

A booming pet industry in the times of Covid-19

1318 days ago